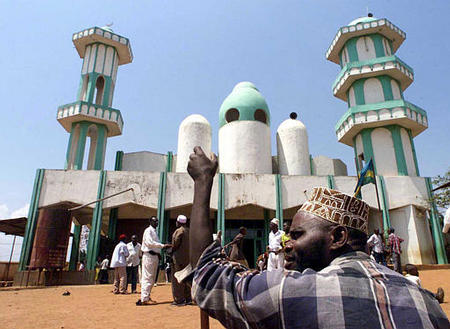

| La mosquée Al Fatah de Biryogo/Kigali |

|

| (Photo AP, 4 oct. 2002) |

Islam Attracting Many Survivors of Rwanda Genocide

By Emily Wax

RUHENGERI, Rwanda -- The villagers with their forest green head wraps

and forest green Korans arrived at the mosque on a rainy Sunday

afternoon for a lecture for new converts. There was one main topic: jihad.

They found their seats and flipped to the right page. Hands flew in

the air. People read passages aloud. And the word jihad -- holy struggle

-- echoed again and again through the dark, leaky room.

It wasn't the kind of jihad that has been in the news since Sept. 11,

2001. There were no references to Osama bin Laden, the World Trade

Center or suicide bombers. Instead there was only talk of April 6, 1994,

the first day of the state-sponsored genocide in which ethnic Hutu

extremists killed 800,000 minority Tutsis and Hutu moderates.

"We have our own jihad, and that is our war against ignorance between

Hutu and Tutsi. It is our struggle to heal," said Saleh Habimana, the

head mufti of Rwanda. "Our jihad is to start respecting each other and

living as Rwandans and as Muslims."

Since the genocide, Rwandans have converted to Islam in huge numbers.

Muslims now make up 14 percent of the 8.2 million people here in

Africa's most Catholic nation, twice as many as before the killings began.

Many converts say they chose Islam because of the role that some

Catholic and Protestant leaders played in the genocide. Human rights groups

have documented several incidents in which Christian clerics allowed

Tutsis to seek refuge in churches, then surrendered them to Hutu death

squads, as well as instances of Hutu priests and ministers encouraging

their congregations to kill Tutsis. Today some churches serve as

memorials to the many people slaughtered among their pews.

Four clergymen are facing genocide charges at the U.N.-created

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and last year in Belgium, the

former colonial power, two Rwandan nuns were convicted of murder for their

roles in the massacre of 7,000 Tutsis who sought protection at a

Benedictine convent.

In contrast, many Muslim leaders and families are being honored for

protecting and hiding those who were fleeing.

Some say Muslims did this because of the religion's strong dictates

against murder, though Christian doctrine proscribes it as well. Others

say Muslims, always considered an ostracized minority, were not swept

up in the Hutus' campaign of bloodshed and were unafraid of supporting a

cause they felt was honorable.

"I know people in America think Muslims are terrorists, but for

Rwandans they were our freedom fighters during the genocide," said Jean

Pierre Sagahutu, 37, a Tutsi who converted to Islam from Catholicism after

his father and nine other members of his family were slaughtered. "I

wanted to hide in a church, but that was the worst place to go. Instead,

a Muslim family took me. They saved my life."

Sagahutu said his father had worked at a hospital where he was

friendly with a Muslim family. They took Sagahutu in, even though they were

Hutus. "I watched them pray five times a day. I ate with them and I saw

how they lived," he said. "When they pray, Hutu and Tutsi are in the

same mosque. There is no difference. I needed to see that."

Islam has long been a religion of the downtrodden. In the Middle East

and South Asia, the religion has had a strong focus on outreach to the

poor and tackling social ills by banning alcohol and encouraging sexual

modesty. In the United States, Malcolm X used a form of Islam to

encourage economic and racial empowerment among blacks.

Muslim leaders say they have a natural constituency in Rwanda, where

AIDS and poverty have replaced genocide as the most daunting problems.

"Islam fits into the fabric of our society. It helps those who are in

poverty. It preaches against behaviors that create AIDS. It offers

education in the Koran and Arabic when there is not a lot of education being

offered," said Habimana, the chief mufti. "I think people can relate to

Islam. They are converting as a sign of appreciation to the Muslim

community who sheltered them during the genocide."

While Western governments worry that the growth of Islam carries with

it the danger of militancy, there are few signs of militant Islam in

Rwanda. Nevertheless, some government officials quietly express concern

that some of the mosques receive funding from Saudi Arabia, whose

dominant Wahhabi sect has been embraced by militant groups in other parts of

the world. They also worry that high poverty rates and a traumatized

population make Rwanda the perfect breeding ground for Islamic extremism.

But Nish Imiyimana, an imam here in Ruhengeri, about 45 miles

northwest of Kigali, the capital, contends: "We have enough of our own

problems. We don't want a bomb dropped on us by America. We want American NGOs

[nongovernmental organizations] to come and build us hospitals

instead."

Imams across the country held meetings after Sept. 11, 2001, to

clarify what it means to be a Muslim. "I told everyone, 'Islam means peace,'

" said Imiyimana, recalling that the mosque was packed that day.

"Considering our track record, it wasn't hard to convince them."

That fact worries the Catholic church. Priests here said they have

asked for advice from church leaders in Rome about how to react to the

number of converts to Islam.

"The Catholic church has a problem after genocide," said the Rev.

Jean Bosco Ntagugire, who works at Kigali churches. "The trust has been

broken. We can't say, 'Christians come back.' We have to hope that

happens when faith builds again."

To help make that happen, the Catholic church has started to offer

youth sports programs and camping trips, Ntagugire said. But Muslims are

also reaching out, even forming women's groups that provide classes on

child care and being a mother.

At a recent class here, hundreds of women dressed in red, orange and

purple head coverings gathered in a dark clay building. They talked

about their personal struggle, or jihad, to raise their children well. And

afterward, during a lunch of beans and chicken legs, they ate heartily

and shared stories about how Muslims saved them during the genocide.

"If it weren't for the Muslims, my whole family would be dead," said

Aisha Uwimbabazi, 27, a convert and mother of two children. "I was

very, very thankful for Muslim people during the genocide. I thought about

it and I really felt it was right to change."

| Saleh Habimana |

|

| The leading muslim cleric (AP, Oct 4, 2002) |

|